Rich, King, Famous: The Founder’s Three Options

Dec 15, 2025

Every founder gets to pick their path—or does their path pick them? A founder must determine whether they want to be rich, king, or famous. Or is that already hard-wired into them?

Noam Wasserman first highlighted this bent in every founder in his thick but helpful book The Founder’s Dilemma. (If you don’t want to read the book, you can see his earlier article about the same idea here.)

His research from the decade he spent exploring founders highlighted two of our three options. He proclaimed that a founder of a company (or a nonprofit) can either maintain control over the enterprise (i.e., be king) or expand the reach, value, and profits (i.e., be rich).

If you’ve ever seen the movie The Founder, the film about the corporate battle between Ray Kroc and the McDonald brothers for control of the fast-food giant McDonald’s, you see it played out. The McDonald brothers wanted to be kings. Ray Kroc wanted to be rich.

But things have changed in the last 15 years. There’s a new option: famous.

Our immediate thought of being famous can be tied to the shallow and slick world of social platform self-interest. YouTube, Instagram, TikTok, Twitter/X—all of it—has created a world where you can be famous and gain millions of followers overnight.

Although that technically fits famous and can be the primary motivator in a founder’s heart, I mean something more substantive. When I say “famous,” I mean to be known for something meaningful, transformative, and helpful. I mean to create or leverage something of consequence and become known for it. Yes, there is a narcissistic edge to chasing recognition, but it is not a predetermined motive or outcome of being known for something.

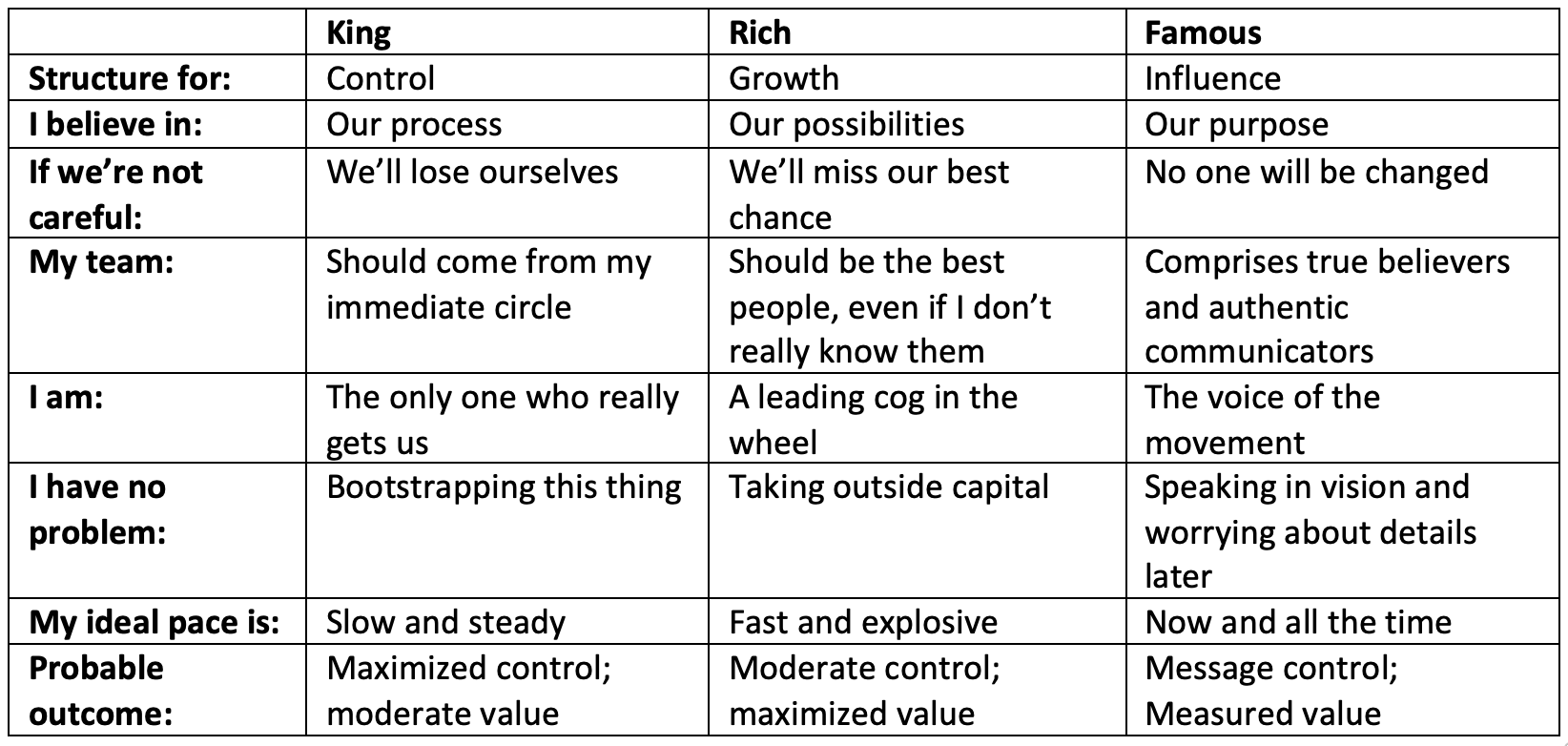

Check out the comparison chart below:

Kings have control issues. They want to make sure that everything is done exactly the right way—meaning exactly the way they want it done. They want final say over hiring, firing, training, spending, and every other –ing.

Rich people, on the other hand, want to create highways to get ideas and products moving. According to the rich, if you do 100 times as much with 95% efficiency, you’ve come out far ahead. So, let’s get things moving.

The aspiring famous want to be known for moving something bigger than themselves forward. Sure, sometimes, it’s really themselves they’re promoting, and egotism (“The cause is me”) is a danger. But for our purposes, we’re looking at those motivated by fame as a means to an end.

With these differences in mind, here are four truths about the king/rich/famous dilemma:

1. It’s part of our wiring.

Among the skills most founders have is a fierce muscle of determination and independence. They are uniquely designed to take ideas from zero to one, as they say. They get things done and make things happen. And that muscle can become stubborn and resistant to outsiders tinkering with their magic.

Other founders are more vision-casting dreamers who somehow attract an operator early on. In that case, the operator is the invisible muscle that moves the company beyond constant concepting and circular dream-casting.

Still, others seem to gather attention without really trying for it. People and money just jump onto their cause or idea.

Every founder has a bent one way or the other. And although that bent has a blue-sky upside, like all our strengths, it also has a downside. Be mindful and self-aware.

2. It’s annoying and heart-wrenching.

Being king, rich, or famous each carries some inherent challenges and risks. What is a danger for one might not even show up for another. For example:

If The Founder is a (mostly) true story, then The Intern is a fictional take on the same idea. Anne Hathaway’s character is a founder whose board is telling her she has to bring on a CEO. She’s torn up about it, convinced that a new CEO will undo much of what she has so lovingly built.

Wasserman found that 80% of founder-CEOs resisted giving up control. Why?

“Because the founder’s emotional strengths become liabilities at this stage. Used to being the heart and soul of their ventures, founders find it hard to accept lesser roles.” – Noah Wasserman

I see this pattern over and over again in my coaching practice, including in the transfer of family-owned companies. Sometimes the heir apparent to the company is a son or daughter who struggles to break away from the founder’s control. It’s why the last and longest of these fifteen tips on family business transfers is, “Let go.”

3. It invites some choices.

On some level, it doesn’t matter whether you choose “king,” “rich,” or “famous.” Going for rich can make you seem like a sellout; kings can seem like power-hungry fools; and the famous get stereotyped as narcissists. The reality, though, is that one is not always better than the other. And each can certainly be balanced with other competencies to provide the best leadership.

One last Wasserman quote: “For founders, a ‘rich’ choice isn’t necessarily better than a ‘king’ choice, or vice versa; what matters is how well each decision fits with their reason for starting the company. … Most founder-CEOs start out by wanting both wealth and power. However, once they grasp that they’ll probably have to maximize one or the other, they will be in a position to figure out which is more important to them.”

In most cases, looking at past decisions—co-founders, key hires, investors, content creation, public messaging—at key junctures will usually reveal which of the rich/king/famous triad you favor and help you see your bias in future decision-making.

4. It adds structure to your weakness.

Peter Drucker once said, “Build on your island of strengths.” I agree with that, but when it comes to founders, they must also do the exact opposite at critical strategic intersections. I believe founders must have enough self-awareness and vulnerability to offset their blind spots and inherent gaps in their leadership regarding their proclivity to be rich, king, or famous.

A founder chasing fame might need someone to turn the idea into a real business enterprise that has cash in the bank every month. A founder wanting to be king might need to get someone in the leadership circle with some independent ideas and thoughts—even though it will create smoke. A founder desiring to be rich might need to have a team member or partner who is overly concerned about the quality and customer experience.

Those are just examples, but you get the idea.

Conclusion

Two final disclaimers:

- I am not making the subtle case that one bent is better than the other. I am making the case that our founder bent shapes everything.

- Secondly, “rich versus king versus famous” is not a total one-or-the-other choice. In some ways, we pick our path, but the truth is that our wiring picks our style. And remember: None of us is driven by just one single motivator. We are all a composite of triggers, appetites, and ambitions. We might have a little bit of one and a whole lot of the other in us.

Steward wisely.

Want to receive Steve's articles in your inbox?

Join 14,000+ leaders who start their week with clarity. Every Tuesday, strategist and advisor Steve Graves shares short, practical reflections from 30+ years guiding CEOs, founders, and entrepreneurs toward flourishing in both business and life.

Free weekly email. Unsubscribe anytime.